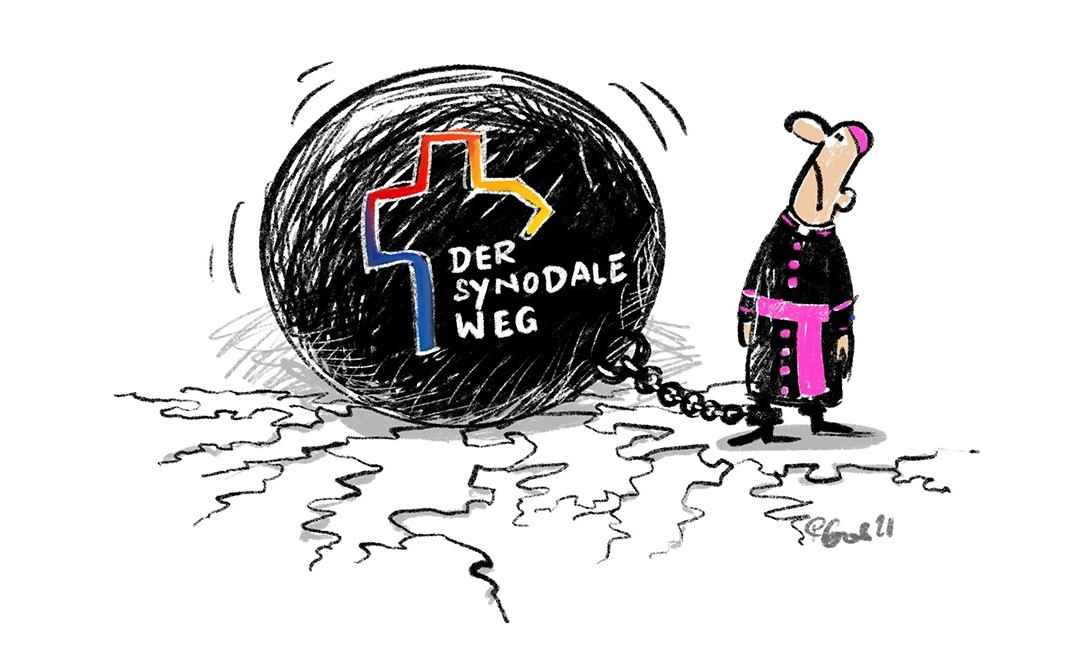

Synodal games seek to bully Bishops into public submission

Cathcon- an important article two days away from the opening of the Fifth and last Synodal Assembly in Germany where they will be voting on ten basic texts (more about them shortly).

It describes how dubious procedure is being followed to seek to deny Bishops (and other) a secret ballot in the hope that they can be bullied either into abstention or a vote in favour of dubious Synod principals.

Never has it been so clear that the Synodal process is all about politics and nothing to do with the Holy Spirit. Whatever their decisions, they cannot be taken up by the wider Catholic Church as the reformers in Germany would love. At the time of the Council, the Rhine flowed into the Tiber through the influence of a coterie of German bishops and theologians including Ratzinger. It cannot be allowed to happen again. The fate of the Church cannot be dependent on a German Interpretation Commission of doubtful legitimacy, shared by the wider process.

--------------------------

When unacknowledged powerlessness

makes you seducible

When voting in the Synodal

Assembly of the Synodal Path, roll-call votes have priority over secret votes. But is that legal? Notes before the 5th Plenary Assembly

By Georg Bier

In a few days, the Synodal Path

will meet for its last plenary session. Among

other things, ten basic and policy action texts are to be voted on. As Beate Gilles, Secretary General of the

German Bishops' Conference (DBK) said at the final press conference of the Spring

General Assembly, the relationship between secret and roll-call votes could

again become an issue.

At the IV General Assembly of the

Synodal Path, the basic text "Living in successful relationships"

failed to achieve the required two-thirds majority of the bishops present. There was great resentment about this, also

because the bishops who voted "No" had not made themselves known in

advance. The Synod Member, zu Eltz

announced that he would request roll-call votes in the future and asked for

clarification as to whether a request for a roll-call vote could be

"counter-ruled" by a request for a secret ballot. The following day he made a corresponding

motion on the Rules of Procedure (GO). The

three-person Interpretation Commission chosen for such occasions met but

without its member Archbishop Schick – the only proven (ecclesiastical) legal

expert in the commission – who did not take part in the Fourth Synodal

Assembly. After the consultation, the members who were present of the Interpretation

commission, the Synod member, Hemel and the Synod member, Wieland, announced

their assessment. The Synod member, Hemel first thanked the Synod member,

Kreuter-Kirchhof “expressly” for their external advice (which suggests a

significant influence of their advice). He

then explained that the members of the commission “saw unanimously that

roll-call voting is given higher priority than secret voting”. Section 6(6) of the GO states that “a vote can

be taken by name upon request, without prejudice to a request for a secret

ballot”. There was "a hierarchy in

the statement." With reference to this vote, subsequent applications for

secret votes were unsuccessful.

Soon after the end of the Fourth

Synodal Assembly, the Würzburg canon lawyer, Martin Rehak worked out with

desirable clarity in another, perhaps not very prominent place that the

information provided by the Interpretation Commission is based on an untenable

assessment of the legal situation. The

positioning of the DBK general secretary at the final press conference gives

reason to expect that the 5th general assembly will also adhere to what the Synodal

Assembly allegedly "adopted" last time. It is therefore appropriate

to explain the events and the legal situation again.

Questionable

First of all, the interpretation

process is questionable: the Commission apparently involved a person who did

not belong to it in the consultation on the interpretation. This also violates the rules of procedure if

this person was not involved in the final "unanimous" decision-making

process. According to Section 7 (4) GO,

it is up to the commission to make a recommendation. It is contrary to this requirement to involve

persons other than those elected by the meeting in any way in the

decision-making process. Otherwise, a Commission

would not have to be specially elected. It

would suffice if the Presidium ad-hoc asked synodal members who seemed suitable

for an assessment.

Considerable doubts exist as to

the impartiality of the interpretation commission. The Synod member, zu Eltz was already

concerned that the request for a roll-call vote could be "thwarted"

by a request for a secret vote, marking the secret vote as a request of dubious

value. The Synod member, Hemel opened their

statement with the "preliminary statement: white smoke!" and at the

end was "happy, together with the assembly, with our Commission, that the

statutes have regulated this in advance with great foresight". Apparently the members of the Commission had a

clear idea of what interpretation they and the Assembly wanted. In any case, impartiality looks different.

The Synodal Assembly, which is

often referred to as "sovereign", was passed over: According to § 7

para. 4 GO, the Interpretation Commission has to submit "decision

recommendations" for the assembly. But

it didn't decide here. The

recommendation was not voted on. Rather,

the moderator thanked the Commission, then stated that "we now have it

clear: Names come before secret ballots" and went straight to the next

item on the agenda. Notwithstanding this, it was repeatedly stated later that

agreement had been reached on the issue.

Misinterpretation of the Rules

of Procedure

Such an approach is problematic

enough. The obviously incorrect interpretation

of the Rules of Procedure weighs much more heavily. For the Interpretation Commission, Section 6

(6) of the GO results in a “prioritization” in favour of the roll-call vote –

it “can be voted on by name upon request, without prejudice to a possible

request for a secret ballot”. The conjunction “without prejudice” should

therefore mean that the roll-call vote must not be damaged by the request for a

secret ballot. This is absurd:

According to the dictionary,

"without prejudice" means: "without harm to ...", "without

disadvantage for ...", "without making any compromises regarding

...", whereby the object, which must not suffer any disadvantage, is

connected to "without prejudice" by a genitive construction. For

example: "Without prejudice to their theological expertise, the members of

the Commission have presented a legally untenable interpretation of the Rules

of Procedure." That means (and is also commonly understood in this way):

that the interpretation is wrong does not call into question the theological

expertise of the interpreters. No one

would think of concluding that theological reputation is being jeopardized by

inadequate interpretation of the law. Another

example: "The advice of the lawyer was - without prejudice to their legal

expertise - incorrect in the matter". Of course, this does not mean that the

incorrectness of the advice is "higher priority" than the expertise

but says the exact opposite.

In legal terms, "without

prejudice" is used in the same sense. For secular law, instead of many individual

documents, a reference to the manual on legal formalities published by the

Federal Ministry of Justice may suffice, where Paragraph 87 states:

"Should other legal norms be applicable in addition to the respective

provision, it can be formulated: 'without prejudice to the rights of third

parties ' or 'without prejudice to the provisions on'. Example: Permission is granted without

prejudice to the private rights of third parties. This means that civil law defence claims by

third parties are not ruled out by the administrative granting of the

permit." Further information is provided by an article by Johanna Wolf

entitled: "Without prejudice" - On the practical understanding of a

popular word in German and European standards and contracts (in:

Juristenzeitung 67 [2012] 31-35). As far

as the relationship between legal rules is concerned, the meaning of the

conjunction is always clear: "The regulation in which the word occurs does

not affect the validity of the regulation mentioned in the genitive."

For the same meaning of ecclesiastical legal language, Canon 861 CIC: According to this, the deacon is (also) the ordinary minister of baptism, but without prejudice to Canon 530, according to which baptism in the parish is primarily the responsibility of the pastor. This means: a deacon may baptize, but that does not change the precedence of the pastor.

Exactly the same is the case with

regard to § 6 Paragraph 6 GO. The

interpretation of the Interpretation Commission runs counter to the clear

meaning of the conjunction "without prejudice" and is therefore

simply excluded. Requests for a

roll-call vote therefore do not affect the request for a secret ballot. According to the clear wording of the

regulation, “prioritised” is the request for a secret ballot. The GO “hierarchized” in its favour. The

following applies: secret votes come before named voted.

Misinterpretation of the Statues

Anything else would also be

incompatible with the statutes of the Synodal path, which as such take

precedence over the rules of procedure (Article 14 statutes, § 17 GO). Article 11 Paragraph 4 of the statute

stipulates that voting is either public or secret. The roll-call vote is that special case of

public voting in which the vote of each individual person is verifiably

documented.

There is a rule-exception

relationship with the (basic) rule: "Voting is public". The exception

is: "Sometimes there is no public voting". The exception is intended

to protect when the application of the rule can become problematic. For this

reason, the statute considers secret ballots to be exceptionally necessary in

two cases: when it comes to personnel issues or when a minority does not want a

public vote. Where the minority is politically located or for what reason they

request a secret ballot is immaterial as of right. It is already clear from

this: If five people request a secret ballot, this request must be followed.

This would be even clearer if the

Statutes said: "At the request of at least five people, a secret vote is

to be taken". Instead, there is not

quite clever talk of “votes that can be held secretly at the request of at

least five members of the synodal assembly”. Nevertheless – as Rehak correctly explained –

what is meant is clear from the point of view as well as from the context:

“can” does not indicate that the protection of minorities is at the discretion

of the Synodal Assembly. "Can" is rather to be read as "an

expression of the authorisation to move away from the principle of public

voting in favour of secret voting in the event of a request by at least five

members."

Absurd consequences

The Fourth Synodal Assembly

showed the absurd consequences of not observing this. The moderation team treated the request for a

secret vote by five people as a request for a rule of procedure and put it to a

vote (which was inadmissible because a request for a secret vote is not

provided for in the exclusive list of possible requests for the Rules of Procedure

in Section 5 (3) GO). The “proposal

motion” clearly missed the simple majority. If this procedure were in accordance with the Statutes

and the Rules of Procedure, the majority could block any request for a secret

ballot. The protective purpose of the exception would obviously have been

undermined, and the exception would not have had to be standardised in the Statutes.

The fact that it was standardized makes

it clear that the concerns of a minority should be protected.

Law before politics

It follows: If the Statutes and Rules of Procedure are applied correctly, a minority of at least five people can enforce a secret ballot. That may be regretted. It can perhaps even be complained by a majority that the priority of the secret ballot allows those Synod members who do not wish to agree to a proposed text (not just the bishops among them) to remain covert rather than show their colours.

However, that does not justify

bending the law, even if it “only” occurs here in the form of rules of

procedure. The General Secretary of the German

Bishops’ Conference (DBK) and the DBK chairman, Bishop Georg Bätzing, explained

at the aforementioned press conference that the statutes and rules of procedure

had weaknesses - which, however, does not apply to the clearly regulated

relationship between roll-call and secret voting. However, it's one thing to regret the legal

position and another to bend it with "interpretations" unworthy of

the name. Rather, this is an expression

of precisely that lack of legal culture that church members (e.g. bishops) reliably

accuse church authorities (e.g. also the Apostolic See) as soon as they

experience themselves as the plaything of arbitrary application of the law.

What is it really about

How could it proceed? According to Rehak, the Synod Presidium could

use the time until the next Synodal Assembly to bring about a correction of the

wrong interpretation of the law and to declare the clear priority of a

requested secret vote for the next general assembly. If this does not happen,

the gathering could show itself sovereign and ensure the observance of the law.

It remains to be seen whether that will

happen.

As things stand, numerous members

of the synod apparently see the roll-call vote as the only chance to get the

bishops to disclose their position, possibly with the expectation that

conflict-averse bishops might prefer an abstention to a clear “no” in this

case. Since abstentions are not counted

due to the vote counting variant decreed by the Synod Presidium, the bishop's

quorum would be easier to reach. The laity could continue to delude themselves

into having advocated reforms with the Bishops. They overlook the fact that they gain nothing.

Bishops who abstain and thus indirectly

enable the acceptance of texts could then nevertheless declare that they had

not agreed and therefore had no reason to implement recommendations in their Diocese.

Bishop Bätzing specifically reminded of

this: "None of the resolutions of the Synodal Path has legal force of its

own accord unless it is converted into law by a bishop".

Conversely, those who are less

open to change may favour secret ballots because they believe—perhaps not

without reason—that anonymity can give some bishops the courage to vote against

and encourage proposals to fail.

The latter can be regretted out

of concern for the future of the Church in Germany. But church reforms are not promoted by bending

the law for their sake and practicing that arbitrariness that church hierarchs

are rightly accused of and which should at least be made structurally more

difficult for the future. Anyone who

would like to do this honestly despite poor prospects should not show

themselves receptive to questionable expedients if necessary. Such seducibility out of unacknowledged

powerlessness did more damage to the cause than a voter defeat.

.jpeg)

Comments