Priest's daughter wins battle with the Church over inheritance

A priest in Perpignan left his entire estate to his hidden daughter. She accuses the diocese of trying to take part of the inheritance.

All for Isabelle, the priest's daughter, or half for the Church? At the beginning of July, the Diocese of Perpignan finally decided to throw in the towel and "purely and simply renounce the legacy of which the Diocese was the beneficiary", i.e. half of an estate valued at €450,000. But for lawyer Jean Codognès, the Church did indeed seek to "rob" his client, Isabelle Ballesteros, a 42-year-old secondary school teacher, before backing down for fear of scandal.

"After robbing this child of her youth and the affection of a father, they wanted to crush the will of this man on the grounds that he belonged to the Church", the lawyer said indignantly. "And they sat on his desire to make human and legal reparation for the suffering endured by his daughter for commercial reasons: to recover the deceased's money.

"All the Bishops of Perpignan knew about it".

The priest, well known in the Perpignan area, was called Lucien Camps. Until his death in November 2021 at the age of 87, he was, for his parishioners, Father Camps, a kind, sympathetic and devoted priest who celebrated masses, weddings and baptisms. But to his daughter Isabelle, born in 1981, he was known as "Dad". And to his two granddaughters, Isabelle's daughters, he was "Grandpa Lucien".

A parallel life, carefully hidden, that the priest led until his death. "All the bishops of Perpignan knew about it, from the moment I was born, right up to the last one", says Isabelle Ballesteros, who welcomes us to her home in a suburban neighbourhood near Perpignan. At her father's funeral, organised by the diocese and celebrated in Perpignan's Saint-Jean-Baptiste cathedral, her daughter was not invited to speak. But the bishop did publicly mention the deceased's daughter and granddaughters.

Before the birth of his daughter, the priest is removed by the bishop

Lucien Camps, a brilliant young engineer, was ordained a priest in 1964 at the age of 30. "My parents met when my mother was a guide leader and my father a chaplain," says Isabelle. A romantic relationship developed a few years later between the priest, now in his forties, and the young woman, 16 years his junior. "My father courted my mother for a long time, but she didn't want the relationship to continue.

Isabelle was born of their love in February 1981. Even before she was born, she says, the bishop was informed of the situation. "He wanted to send my father to Africa, but he refused. He was sent away, for two years, to Toulouse. "It was a punishment. We moved the problem around in the hope that the mother and child wouldn't come back and that the priest would continue to live his life as a priest.

"We went to the cinema or to a restaurant in another department".

Officially born "of unknown father", according to the civil registry, little Isabelle never stopped asking for her father. On the eve of her 6th birthday, he finally came into her life. Isabelle's mother, a care assistant, lives with her daughter and supports them alone. Lucien visited them regularly. "He'd come on Tuesdays, come back on Saturdays, spend the night with us, then leave to celebrate mass on Sunday morning. And sometimes we'd get together on a Sunday afternoon for a family walk. Never on the nearby beaches or in the centre of Perpignan.

"The first time I went to the cinema with my father was in Narbonne, 80 kilometres from Perpignan. And when we went to the restaurant together, it was in another département. Every year, the priest goes on holiday with his family, to Brittany, Normandy, Paris, Portugal... "There, we didn't need to go to the cinema. There, we didn't need to hide.

But when he sees someone he knows in the street with his daughter, he introduces her as his "goddaughter". Isabelle was forbidden to visit her father, "because he lived in a building where other priests were staying". When asked what her father did for a living, the little girl replied that he was a computer specialist. "He was in charge of IT for the diocese".

Present at her daughter's wedding

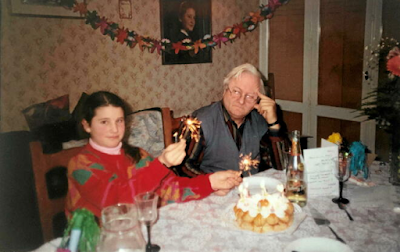

At Christmas, his daughter's birthdays, her communion, her engagement, Father Camps was always present. At her wedding in 2006, he was there, a little in the background: he didn't bring his daughter to the altar, he didn't celebrate the wedding, as she had asked, he didn't sit at the head table with her mother. But he was present, and embraced his only daughter in the photos of the ceremony.

But he did not soothe his daughter's pain. "I knew from the age of 7 that I was the daughter of a priest. I was angry, I suffered from being deprived of my father on a daily basis, from having to hide who he was". And to be deprived of part of her roots. "On my mum's side, my family tree was complete, but on my dad's side, it stopped at dad". She never met her paternal grandmother, who died at the age of 103. And she probably didn't even know she existed.

4,000 "children of silence" in France

The priest never officially recognised his daughter. But in 2011, he made her his universal legatee. On the very day of her father's death, Isabelle discovered, in the notary's office, that she was inheriting his property... and that he had drawn up a second will, six months before his death, leaving half of his estate to the diocese. For Isabelle, it was as if her father had been stolen from her a second time: "The emotional shock tore me apart from the inside. "The diocese took advantage of Lucien Camps' weakness," says his lawyer, Jean Codognès.

The new will was written in a diocesan nursing home, where the priest had been admitted shortly before. An expert psychiatrist diagnosed a state of "dementia" that "did not allow Mr Camps to draw up a will". On the contrary, the Diocese's lawyer considers it "highly unlikely" that the two notaries present would have "agreed to receive the will" of the priest if they had "judged him to be insane".

But the new bishop, who took office in June, preferred not to. Isabelle will inherit her father's estate alone. Living in hiding is terrible and very painful for the children of priests," she says. Marriage for priests wouldn't solve all the Church's problems, but it would make these children happy. The association Les Enfants du silence, which brings together the children of priests, estimates that there are 4,000 of them in France.

Cathcon: Post-conciliar infidelity

.jpeg)

Comments